by Heather Allen | Mar 25, 2022 | Advocacy, Net Metering, PSC Priorities, Solar

RENEW Wisconsin, together with a coalition of Clean Energy Advocates (Clean Wisconsin, Environmental Law, and Policy Center, Vote Solar, The Nature Conservancy, Wisconsin Conservation Voters, and the Wisconsin Health Professionals for Climate Action), submitted comments this week to the Public Service Commission in favor of protecting and improving net metering in Wisconsin.

The Commission asked for remarks on four key questions and shared a 60-page memo from the Regulatory Assistance Project describing net metering policy issues, changes to net metering in other states, and several other aspects for consideration. The comment period closed on Tuesday, March 22, 2022.

Wisconsin’s customer-owned solar market is falling behind our neighboring states due to a patchwork of service terms and artificial market barriers. Our coalition comments highlighted several key factors contributing to the issue:

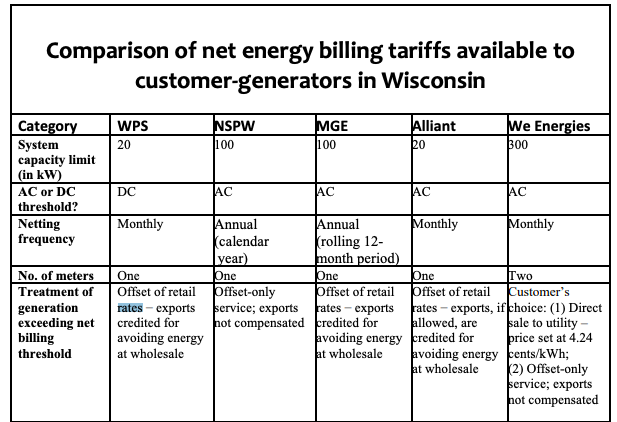

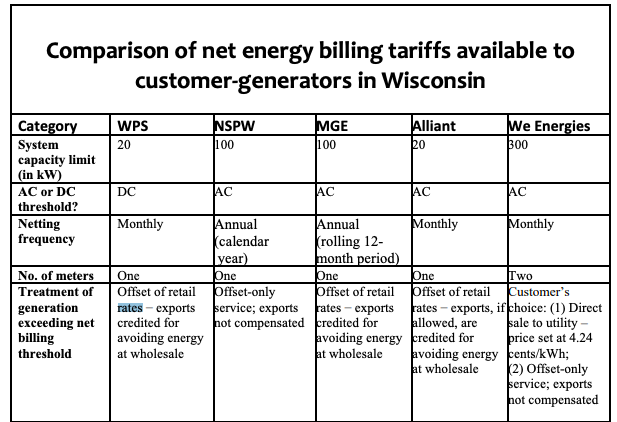

- The absence of a statewide net energy billing policy has fostered an inconsistent and confusing patchwork of tariffs across Wisconsin.

2. Low net energy billing ceilings and low export rates effectively exclude many larger customers from investing in solar systems.

3. Encroachment of utility-owned DG reduces behind-the-meter installation opportunities for customers and solar contractors.

4. The lack of clarity over third-party financing hampers the solar marketplace.

Solar installers, solar customers, clean energy advocates, and climate activists submitted comments echoing these themes. Here are some quotes from the commenters:

“The time has come for the Wisconsin Public Service Commission (WiPSC) to take a customer-centric approach to address the need for dramatic greenhouse gas emission reductions.”

Kerry Beheler and Gary Radloff

Wisconsin GreenFire

“Larger commercial and industrial customers should be allowed to net meter on larger projects that help them displace a greater percentage of their usage with on-site renewable generation. Adjacent states have raised net meter limits above 1000 kW for these customers. State goals of increased renewable energy are efficiently met with an on-site generation that is offsetting load, and this also possibly reduces the need for additional transmission infrastructure. Net metering is one good tool encouraging on-site renewable generation.”

Weselley Slaymaker

“I support a robust net metering policy for Wisconsin. The adaptation of solar power is critical for our energy independence and to mitigate the impact of climate change.”

Megan Stansil

RENEW and its allies explained their priority to improve net metering in the near term to “make net billing tariffs more consistent across Wisconsin utilities.” But we also urged caution that no other reform that could diminish customers’ value proposition for investing in these grid-beneficial technologies should be pursued before reaching much higher solar penetration levels and analyzing the impact of such potential changes.

Net metering is a valuable tool that helps customers generate their energy in a manner that provides both system and public benefits, including carbon emission reduction and economic development. It drives solar deployment and is easily understood and accessible to customers. RENEW will continue to participate in this conversation at the Commission and share results as this process moves forward. Wisconsin can improve customer transparency with a more uniform statewide approach but should be very cautious about risking the benefits of distributed generation by altering rate design.

by jboullion | Jan 16, 2015 | Net Metering, Uncategorized

In the last three years, several Wisconsin utilities have proposed changes to their net metering service in an effort to reduce the value proposition of solar generation for host customers. One way to accomplish this objective is to dramatically shrink the duration of the netting period. In Wisconsin several utilities have sought permission to reconcile output and consumption on a monthly basis. Twice in the last two years, a majority on Wisconsin’s Pubic Service Commission have signed off on utility requests to limit the netting period to the monthly billing period, We Energies being the latest to receive approval to impose monthly true-ups.

As the article from Midwest Energy News’ Kari Lydersen below demonstrates, the greater the output from a PV array relative to the host customer’s consumption, the higher the likelihood that a portion of that system’s production will be compensated at a substantially reduced rate. Depending on the utility, that lower rate can be 75% less than the retail energy rate offset. This policy is particularly damaging to residential and small business solar producers, due to strong seasonal swings in both system output and consumption.

In Wisconsin, solar ‘new math’ could equal big impacts

Posted on 01/16/2015 by Kari Lydersen

|

Solar panels on a home near Milwaukee.

(Photo by mjmonty via Creative Commons) |

For tourists, the “shoulder seasons” in the spring and fall are times to get cheap deals in ski resorts or beach towns that cater to summer and winter crowds.

For people with solar power on their homes, these seasons are when their solar installations are most likely to be producing more energy than the home actually needs. These “shoulder months,” as RENEW Wisconsin Policy and Program Director Michael Vickerman frames it, are at the crux of one of the ways solar power is under attack in Wisconsin.

The Wisconsin Public Service Commission recently approved three controversial rate cases proposed by We Energies, Wisconsin Public Service Corporation (WPS) and Madison Gas & Electric, which all will make it much less favorable or feasible to install solar panels on a home or small business.

We Energies, the most significant case, includes a provision that will change how the utility compensates consumers for sending energy back to the grid, by changing from annual to monthly “true-up” net metering calculations.

This may sound like an arcane modification. But Vickerman and other solar advocates say it means people will be compensated drastically less for the energy they send back to the grid during the spring and fall, and they are likely to build smaller solar installations as a result.

Unless an expected legal challenge to the Public Service Commission decision is successful, the true-up change will take effect in January 2016. WPS has done its calculations on a monthly basis since a 2013 rate case (docket number 6690-UR-122 on the commission’s website).

“It definitely is not reflective of best practices to switch from annual to monthly” true-ups, said Sara Baldwin Auck, regulatory program director of the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC), which publishes an annual report called “Freeing the Grid” scoring states’ net metering policies.

“Net metering policies are a compilation of multiple pieces, they all add up to favorable [or unfavorable] conditions and terms for the customers who are seeking to invest in onsite renewable energy and take more control of their energy future and energy bills. It’s a little tough to say whether the true-up issue is the lynchpin, but I will definitely say that this issue ranks higher than others as far as contributing to the overall best practices.”

The math

Typically, at the end of the year utilities tally up how much energy a customer has used and how much they have sent back to the grid from their solar installations. Then the customers are either charged or compensated for the difference, or the energy they have “banked” may be put toward the coming year’s usage.

When someone produces more energy than they have used, there’s the question of how much to pay them for that energy sent back to the grid. This is where net metering policies defined by different state laws or determined by different utilities can vary significantly.

The customer with solar panels can be compensated at the retail rate – the cost they would have paid for electricity at that time; or the “avoided cost” rate, the amount the utility estimates it saved by not having to provide that amount of power to other consumers on the grid. The rate may also be determined through a formula based on several market factors.

Retail and avoided cost rates are significantly different. Avoided cost rates for Wisconsin utilities are 3 to 4 cents per kWh, while retail rates are around 11 to 14 cents per kWh.

When a solar installation produces less energy than a home uses during the true-up period, the way surplus energy is compensated is irrelevant, since there is none. But when someone is sending significant solar energy to the grid, different rates of compensation can add up.

That’s where the shoulder seasons become important. Most Americans use their highest amounts of electricity in the summer, with air conditioners running. Winter also usually means high electricity use, with more lights on when the sun sets early and electricity sometimes used for heating the home or heating water. In the spring and fall, by contrast, household electricity use tends to be lower. That’s when solar installations are most likely to send more electricity back to the grid than the home uses.

If net electricity consumption and generation is all tallied up at the end of a year, people essentially get to “use” their springtime solar power in the summer or winter when their demand is higher. But if the balances are tallied every month, consumers will often end up getting low avoided cost rate payments for their surplus energy during the shoulder seasons, then buying more electricity at higher retail rates in summer and winter.

We Energies spokesman Brian Manthey said, “Monthly net metering more accurately and more fairly values distributed generation by crediting on-peak use at the on-peak rates and crediting summer generation at typically higher summer-based rates.”

“To set the buyback rate at something higher than avoided cost for customer-generated energy would set an inappropriate price signal and would be unfair to customers without their own generation,” Manthey continued.

How much does it matter?

Vickerman said surplus energy payment and true-up policies are typically figured in when someone decides what size solar installation to put on their home. If they won’t be paid much for unused energy, they may choose a smaller installation…meaning less clean energy on the grid.

Vickerman made these points in testimony before the Wisconsin Public Service Commission in 2013 regarding WPS’s change to monthly true-ups. He noted that companies who advise customers on installing solar use sophisticated “solar math” to decide what size system is most financially efficient, and the true-up period is an important consideration in that equation.

Vickerman gave an example of a 4,500-4,900 kWh system in Green Bay. That would seem a good fit for a home using 5,000 kWh per year. But given typical monthly fluctuations, based on widely accepted models, he estimated that household would have to sell 561 kWh per year back to the utility at the lower avoided cost prices.

That would represent a loss of about $55 under monthly true-ups compared to annual calculations. That would increase by 10 percent the time it would take the solar system to pay for itself in energy savings. Faced with that situation, Vickerman said, a customer might choose a smaller solar array.

“You need to look at all the pieces,” of a net metering policy, said Baldwin Auck. “One element can really have a domino effect on whether that policy is ultimately effective in encouraging people to install these systems.”

The national scene

Baldwin Auck said that 22 states have “some form of annual true-up.” The “ideal scenario” for net metering, she noted, is “indefinite rollover,” where the excess energy someone has sent to the grid is perpetually credited to their account in a situation akin to a meter literally running backwards.

In California, state law says that a customer cannot be required to true-up more frequently than once a year. However some utilities offer customers the option to true-up monthly, saying it helps them avoid “surprise” charges once an annual bill is due.

PG&E in California, for example, calculates net metering on an annual basis, and at that time pays customers an annual rate of 4 cents per kWh for the surplus energy. Southern California Edison allows customers to receive a check for surplus energy at the end of the year or to roll over their credit into the next year’s billing cycle.

California received an A grade for net metering policies in the 2015 Freeing the Grid report. California also has more friendly solar policies on other fronts, for example only solar installations of 20 kW or less typically qualify for net metering in Wisconsin, whereas California utilities accept installations up to 1 MW.

Illinois, Michigan, Iowa, Indiana and Minnesota all got B’s for net metering policies in Freeing the Grid, and Ohio got an A.

“The monthly true-up is much less common, and there is a strong correlation between states that have received an A or B grade on the scorecard, and annual true-ups,” Baldwin Auck said.

The value of electricity

Clean energy groups plan to challenge various aspects of the We Energies rate case. First they must file an administrative challenge with the Public Service Commission. If the commission denies that

appeal, they can file a lawsuit in state circuit court.

“We will ask the commission to reconsider, though we have a pretty good idea what the commissioner will say,” said Vickerman. “It’s a process we have to go through.”

The commission’s approval of the MG&E rate case is also likely to be challenged. However the MG&E case does not change the true-up period.

Another utility, Alliant Energy/Wisconsin Power and Light does not have a full rate case pending, but it recently went through a smaller proceeding before the Public Service Commission. Wisconsin Power and Light already trued-up customers with solar monthly. But they paid the retail rate rather than the avoided cost rate, so the monthly calculations raised no concerns. A change which took effect January 1 (docket number 6680-FR-107)) means that now Wisconsin Power and Light pays separate retail and avoided-cost rates.

“They were already doing the net calculations every month, but it didn’t matter when every kilowatt hour got the same credit,” said Vickerman. “Now they’re switching from a one-tier to a two-tier structure, and suddenly it matters.”

Renew Wisconsin challenged the Wisconsin PSC change, and ultimately came to a settlement that allows more customers to continue for a longer time grandfathered in under the old system. The settlement means the utility increased from five to 10 years the time grandfathered-in solar operates under the old system. And the settlement meant solar installed up until December 31, 2014 is grandfathered in, as opposed to the utility’s proposal of July 2014.

“We’re not happy with that, but on the other hand it could be much worse,” said Vickerman of the settlement.

Baldwin Auck said that in the debates over true-up policies and surplus energy rates, she hopes people don’t lose sight of the forest for the trees.

With a solar installation “You’re reducing onsite consumption, and on top of that giving energy back to the grid,” she said. “The credit a customer receives for that energy should be reflective of the full value of that electricity.”